Primary Prevention

What is primary prevention?

Even though violence against women is widespread and serious, the good news is that it is also preventable.

‘Primary prevention’ means addressing the drivers of violence against women by promoting gender equality and addressing the social norms, practices and structures (key drivers) that drive violence against women or create the context for violence against women to occur. The aim of primary prevention is to stop violence before it happens.

While primary prevention may seem difficult to achieve, it is an approach that has been used successfully in the past on a range of other public health issues in Australia – like smoking and road safety.

(OurWatch, 2021)

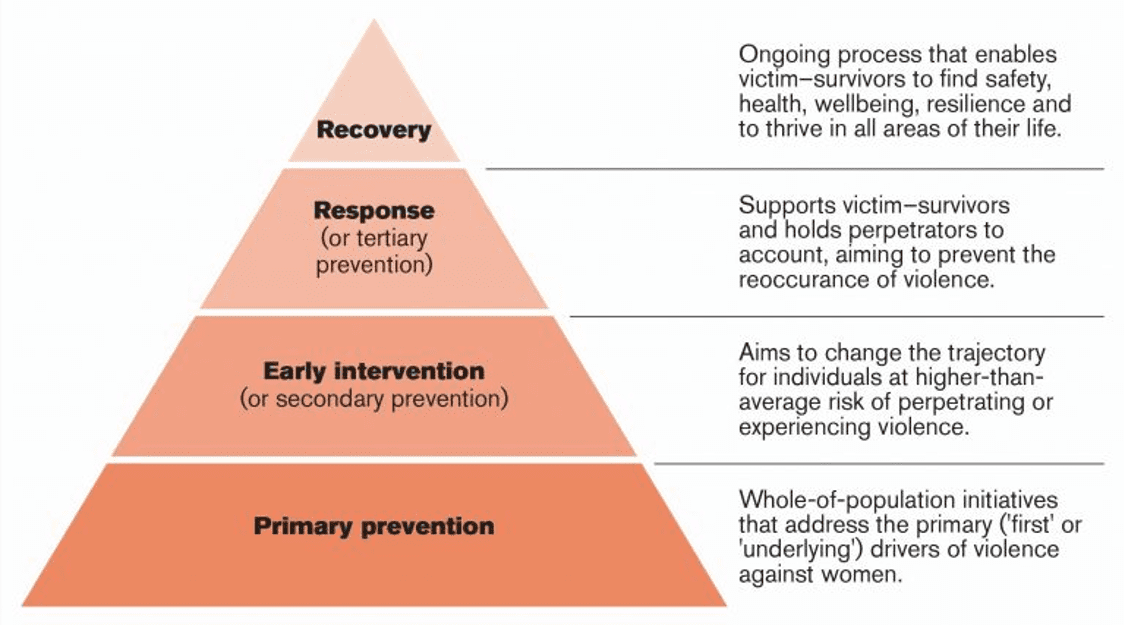

Primary Prevention:

Whole-of-population initiatives that address the primary (’first’ or underlying) drivers of violence against women.

Early Intervention:

Aims to change the trajectory for individuals at higher-than-average risk of perpetrating or experiencing violence.

Response:

Supports victim–survivors and holds perpetrators to account, aiming to prevent the recurrence of violence.

Recovery:

Ongoing process that enables victim– survivors to find safety, health, wellbeing, resilience and to thrive in all areas of their life.

What is violence against women?

“Violence against women is any act of gender-based violence that causes or could cause physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of harm or coercion, in public or in private life.”

In Australia, violence against women is called many different things, including domestic violence, family violence, intimate partner violence, coercive control, online abuse, stalking, workplace sexual harassment, street harassment and sexual assault. Our definition includes all these forms of violence against women.

(OurWatch, 2021).

What drives violence against women?

There is now a significant body of evidence that shows that gender inequality is a is a consistent predictor or “driver” of violence against women.

Gender inequality is where women and men do not have equal social status, power, resources or opportunities, and their voices, ideas and work are not valued equally by society.

Violence against women is not caused or determined by any single factor. But as the number of relevant factors and their degree of influence increases, so does the probability of violence against women. These factors are termed ‘gendered drivers’ because they arise from gender-discriminatory institutional, social and economic structures, social and cultural norms, and organisational, community, family and relationship practices that together create environments in which women and men are not considered equal, and violence against women is both more likely, and more likely to be tolerated and even condoned (OurWatch, 2021).

Within this context, the following expressions of gender inequality have been shown in the international evidence to be most consistently associated with higher levels of men’s violence against women:

Driver 1: Condoning of violence against women.

When societies, institutions or communities support or condone violence against women, levels of such violence are higher. Individual men who hold these beliefs are more likely to perpetrate violence against women. Condoning of violence against women occurs both through attitudes and social norms and through legal, institutional and organisational structures and practices that justify, excuse or trivialise this violence or shift blame from the perpetrator to the victim. Violence against women who breach socially accepted roles or identities, such as sex workers or trans women, or women who are seen as ‘promiscuous’ or intoxicated is more likely to be condoned, and there is a particular tendency for violence against women with disability to be downplayed or trivialised, and for violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to be ignored.

Driver 2: Men’s control of decision making and limits to women’s independence in public and private life.

Violence is more common in relationships in which men control decision-making and limit women’s autonomy, have a sense of ownership of or entitlement to women, and hold rigid ideas on acceptable female behaviour. Constraints on women’s independence and access to decision-making are also evident in the public sphere, where men have greater control over power and resources. All these forms of male dominance, power and control and limits to women’s autonomy collectively contribute to men’s violence against women by sending a message that women have lower social value and are less worthy of respect.

Driver 3: Rigid gender stereotyping and dominant forms of masculinity.

Promoting and enforcing rigid and hierarchical gender stereotypes reproduces the social conditions of gender inequality that underpin violence against women. In particular, stereotypes of masculinity play a direct role in driving men’s violence against women. Men who form a rigid attachment to socially dominant norms and practices of masculinity are more likely to demonstrate sexist attitudes and behaviours, hold violence-supportive attitudes and perpetrate violence against women. Globally, rates of violence are higher in societies, communities and relationships where there are more rigid distinctions between the roles of men and women, and more stereotypical notions of the ‘ideal’ man or woman, and where dominant forms of masculinity are rigidly adhered to.

Driver 4: Male peer relation and cultures of masculinity that ephasise aggression, dominance, and control.

Male peer relationships (both personal and professional) that are characterised by attitudes, behaviours or norms regarding masculinity that centre on aggression, dominance, control or hypersexuality are associated with violence against women. In such peer groups, adherence to these dominant forms of masculinity increases men’s reluctance to take a stand against violencesupportive attitudes, and can increase the use of violence itself. Structural factors – such as poor organisational cultures, inadequate policies and insufficient penalties – can reinforce, support or excuse violencesupportive attitudes and behaviour, particularly in male-dominated organisations and contexts.

|

OurWatch Change the Story, 2021 https://plan4womenssafety.dss.gov.au/resources/what-is-violence-against-women/ |

How do we prevent violence against women?

To stop violence against women, we have to take action to address each of the 4 drivers of violence against women.

No one person or organisation can bring about an end to violence. A collective, community wide effort is needed, by addressing the drivers of violence against women across all areas of society. Individuals, families, communities, organisations and systems (like the legal system) all play a role.

Here are some examples of actions that address each of the drivers at different levels of our community:

Action 1 : Challenge condoning of violence against women.

This involves challenging the beliefs that justify, excuse, trivialise or downplay violence against women, or shift blame from perpetrators to victims, as well as challenging the ways these beliefs are upheld through things like workplace practices and laws.

Examples of actions that challenge the condoning of violence include:

- Calling out ideas like ‘why did she get so drunk?’ or ‘why didn’t she fight back?’, when they’re used to shift blame for violence – such as when they’re featured in media.

- Proactively implementing reasonable and proportionate measures within organizations and businesses, in accordance with the positive duty obligations outlined in the Sex Discrimination Act 1984, aimed at preventing sexual harassment and discrimination.

Action 2: Promote women’s independence and decision making in public life and relationships.

This means promoting women’s independence in their relationships and families, as well as promoting women’s access to resources and decision-making power in public life, including in workplaces and parliaments.

Examples of things that promote women’s independence and decision-making in public life and relationships include:

- Programs that increase the number of women running for public office through training and networking opportunities.

- Workplace action plans for recruiting and retaining women in leadership positions – including things like addressing unconscious bias in recruitment.

- Strengthening women’s economic security through things like subsidised child-care.

- Programs that work with individuals to promote healthy and respectful relationships.

Action 3: Build new societal norms that foster personal identities not constrained by gender stereotypes.

This involves challenging beliefs about how men and women should behave – and what they’re capable of – as well as challenging the ways these beliefs are upheld through social practices.

Examples of actions that help build these new social norms include:

- Providing baby change tables in men’s toilets as well as women’s toilets

- Social marketing campaigns about why gender stereotyping is limiting.

- Programs that work with young people to challenge rigid gender roles and identities for women, men and people of other genders.

Action 4: Support men and boys to develop healthy masculinities and positive, supportive male peer relationships

This involves supporting men and boys to develop healthy ideas about what it means to ‘be a man’ – and positive relationships with other men, that are not built on showing aggression, dominance, control or ‘hypersexuality’ (through things like sexual boasting).

Examples of actions that support men and boys to develop healthy masculinities and positive peer relationships include:

- Working with male sports teams to build their understanding of sexual consent, mutual pleasure and the unrealistic nature of pornography.

- Workplace initiatives that promote inclusive forms of leadership, not based on aggression or dominance.

(OurWatch, 2021) (Human Rights Commission, 2023)

What are the benefits of a gender equal world?

Gender equality is good for everyone — women, men, boys, girls and people who are gender-diverse.

Unequal societies are less cohesive. They have higher rates of anti-social behaviour and violence. Countries with greater gender equality are more connected. Their people are healthier, safer and have better wellbeing.

Advantages of gender equality for individuals

In Australia, one in three women experience men’s violence. Men also experience men’s violence and other negative impacts on their lives — including mental illness and suicide — due to rigid gender ideas about what it means to ‘be a man’.

In a more gender equitable society, women, men and people of all genders could:

- Live their lives free from the men’s violence, and the threat of it

- Express themselves in ways that felt right, for them, and that promoted their health and wellbeing.

Advantages of gender equality for families

Even though women make up nearly half of the paid workforce in Australia, they still spend almost twice as many hours a day as men on unpaid housework and childcare.

A more gender equitable division of housework and childcare could make for:

- Happier relationships — research shows that gender imbalances around housework can lead to relationship friction and increase the likelihood of divorce.

- Happier children — teens in countries where social norms support both parents’ involvement in childcare report higher levels of life satisfaction

Advantages of gender equality at school and work

Even though Australia ranks number one in the world for women completing education, we rank 49th for women’s economic opportunity and participation. In 2022, women continue to be over-represented in areas of study that are linked to lower earning industries and women’s average full-time earnings are 14% less than men’s.

Gender equality in educational outcomes and at work could mean:

- More prosperous economy — the Australian economy would gain $8 billion if women transitioned from tertiary education into the workforce at the same rate as men

- Reduction in women’s poverty and homelessness, especially later in life.

Advantages of gender equality in public life

We are yet to see a representative number of women reach the highest levels of business and politics in Australia. Only 14 CEOs of Australia’s top 200 companies, and only 39% of federal parliamentarians, are women.

Gender equality in public life could mean:

- More profitable businesses — businesses with at least 30% women in leadership positions are 15% more profitable.

- Fairer, more cohesive societies — women in positions of authority tend to resolve national crises without resorting to violence, advocate for social issues that benefit all and allocate greater proportions of national budgets to health and education.

(OurWatch, 2023)

What about violence against men?

All forms of violence perpetrated towards humans is unacceptable and must be taken seriously. There are specific gendered patterns in offending, experience of violence and impact, that need to be considered.

- Both men and women experience violence – but they experience it differently.

- About 95% of all victims of violence, whether women or men, experience violence from a male perpetrator.

- Women are more likely to know the person who is abusing them – it’s often a current or previous partner, and the violence usually takes place in their home

- The overwhelming majority of domestic violence and sexual assault is perpetrated by men against women and is likely to have more severe impacts on female victims.

- Women are more likely than men to be injured, require medical attention or hospitalisation, or experience mental health impacts as a result of intimate partner violence, are more likely to experience sexualised violence, and to report fearing for their lives.

(Preventing Violence Together, 2023) & (OurWatch, 2021)